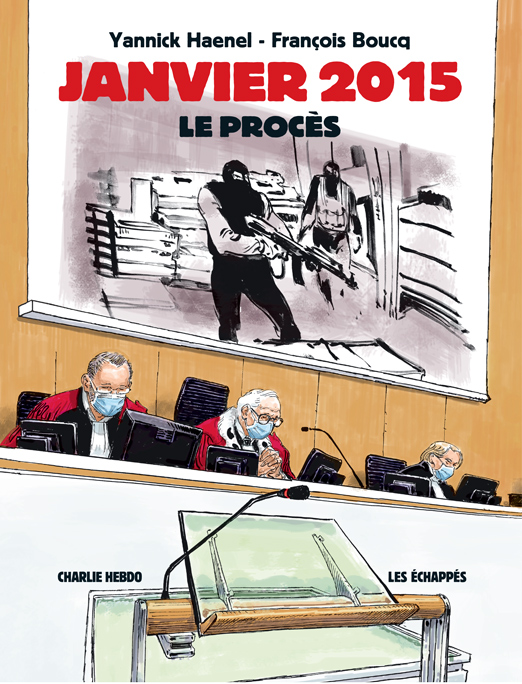

INTERVIEW WITH Yannick Haenel

Delphine Horvilleur People often ask me how I manage to deal with death, mourning, and tragedy on a daily basis. How did you manage to listen to people talk about their experiences every day? Did you prepare yourself physically or spiritually for these face-to-face discussions?

Yannick Haenel I was totally unprepared, but I spend my life writing and this had to be written. I was able to keep the courtroom and my home separate. I wrote at home. I quickly realized it was impossible to write immediately after returning from an 8-hour hearing. I took thirty pages of notes each day. Originally, I had wanted to transcribe absolutely everything I’d heard, but it was too much. I have eight hundred pages of manuscript that I don’t know what to do with. So I took notes, I’d go to sleep, and then at 4 a.m., in my house, this other space, something would emerge from the encounter with the dead and the living. The words I had held fast to all day long transformed into something else that had to come from me. Writing is my moral code, it’s my way of immediately transforming what I experience, hear, and suffer—not into a defense, but into a vulnerability that is addressed. That would be an improvised definition: an addressed vulnerability.

I realized that in order to live up to the words that had come from the witnesses, plaintiffs, and defendants, who were all in some way related to the killing, it wasn’t a good idea to protect myself or give myself time to rest—that everyone had suffered, even the accused. Yes, even the accused had suffered the fact of being involved in the killing. I hadn’t been there, but I was speaking for people who had survived it. Inventing something was an immediate necessity, so I invented what I know: words, text. The decision to stick close to death was sheer madness. I was constantly telling myself I didn’t want to forget the victims of Hyper Cacher, of Montrouge, and of Charlie Hebdo. But I don’t know what it means to “not forget the victims”. I feel it involves the notion that grieving includes forgetting, that we are making a transaction with memory. And that it was my job to give the victims a presence—the act itself was somewhat thaumaturgical. What I was concerned with did not have to do with the trial, I was immediately swept into the realm of the metaphysical.

Stéphane Habib I am wondering about your relationship to writing, particularly with this book. What is literature, for you?

This book requires a microscopic, very meticulous reading in order to assess the intensity of what you are putting into play. The assembly of these texts seems, to me, one of the greatest meditations on justice that I have read in a very long time. I want to clarify that, for you, justice cannot be separated from speech acts and truth. The text seems to braid together these themes: justice/speech/truth. These are three recurrent motifs in your work, perhaps going back as far as your first book. In the preface you talk about “a human and political truth that makes itself heard with each passing day” and you write that “death does not have the final word; this is called justice”. And in the next sentence, you make fundamental use of language by talking about the “survivors”.

YH They wanted to be called that, Simon Fieschi and Riss. It was a very important moment during the trial when this distinction was used by those who had suffered. The victims argued they wanted to turn victimology against society. So they said, “We are survivors.” Riss went as far as to say, “We are innocent.” The word survivor is reconstructed in the trial.

SH When we read the book, we see that it is a story of survival: there are things that are constantly coming back to haunt us. And that it’s a book that is created out of a concern for survival. Which is, in my opinion, the strictest definition of politics. And there is a fourth thread throughout that you define politically, which is the term “freedom.” I’ll quote the last few words of the preface: “Thanks to this trial, but also thanks to him [here you pay tribute to Samuel Paty] we are now freer: we cannot stop thinking, and only by thinking will we grow.”

For you, aren’t literature and writing a recreation of both the oldest law of metaphysics and the most fundamental questions of ethics and politics and poetry?

YH The trial completely stripped me. It turns out that with each book we write, at the very least we end up stripped down, starting back at zero. In fact, all the great signifiers you are talking about are there, and they are certainly not big words—they are little words, the cracks in the rock where the initial voice appears. I was willing to be as vulnerable as possible—which I didn’t have to choose—, so that I could open myself to something that is not simple, where at every moment the words were knotting together which created and founded and deconstructed a parliament of voices at any moment.

I had never set foot in a courtroom before, and that was the first reason I hesitated when the invitation was extended to me. The second reason was that I would be writing for people who were revisiting it. I feared that my words wouldn’t accurately represent the experiences of those who had been at the scene of the crime. And yet it was precisely this opportunity for discrepancy that steered my moral code. The freedom I was given, even if this meant wandering in the Mallarméan sense, brought something to the people who had lived through it, at least according to them. It’s not that I was expecting truth from justice. I listened to everybody who came, not only during the trial but also afterwards, and everyone told me they expected truth from justice. That surprised me, since truth was taking place at every moment, and I told myself it wasn’t about expecting truth, that it was constantly present. I was confronted in a temporal, urgent way at every instant, since each person who spoke was participating—I’m not saying they spoke the truth, but they were participating—in this sequence that does not exist in society. The parliament of voices, the manner in which these voices spoke, this democracy of speech that invariable includes contradiction, that doesn’t exist in “real life” as children would say. And at that moment, it did exist. It was incredible.

DH In Judaism, truth is one of the names of God: Emet. It is one of the pillars of the world. And it is a very special word, because it is written using the alphabet’s first letter, middle letter, and last letter. And so truth is the tripod of the alphabet. The world is held up by truth, which acts as a balancing force.

As I was listening to you, I was also thinking of the notion of justice. In the Jewish tradition, we say a prayer to accompany the dead at the graveside, the El Malei Rachamim. It is for the ascension of the soul of the departed, which connects the living to the dead. In this prayer, we say something strange: that we pledge to give tzedakah in memory of the departed, a term that is often (poorly) translated as “charity”. But tzedakah actually means “justice”. This prayer tells us that what we can do for the dead is to care about justice. What the dead expect of us is to put our efforts into tzedakah, or social justice for the living. Caring about justice is done in memory of the dead. What I found disturbing was how your writing influenced my “liturgy” during this period. It was around the time of the Tishrei holidays, and I was wondering what to talk about during my Yom Kippur sermon, and this was also when the Hyper Cacher trial was happening. I read your column about Zarie Sibony, where you talked about the world above and the world below. Which is incredible, because Yom Kippur is a summons to a trial: we are all summoned to act as defendants in a collective court. And the prayer begins with these words: “In a convocation of the heavenly court and a convocation of the lower court, we hereby grant permission to pray with transgressors.” And Kippur begins. It was disturbing to see, through your text, the connection between these worlds.

YH The experience I had within this astonishing space, during these hearings, that kept churning out words, made me think constantly of this Levinas quote: “Truth presupposes justice.” We are in something that necessitates a code of ethics: truth is nothing without ethics, knowing that it demands care, and listening is a form of care. It is true that, for me, the trial made me put writing to the test: does someone who has the strange habit of writing, this liturgy—perhaps without a god, but with his own god—hear something that the trial itself does not? Since I had the chance to produce every day, to write a book in public, I became the trial’s narrator without admitting it. That’s crazy. And before opening the court proceedings, the president of the court would read what I’d written from the day before. The question of vulnerability was necessary because no one power can be capable of hearing the piecemeal, powerful things that come from weakness. You have to be extremely weak. I kept getting weaker, I was shackled everywhere, because this weakness became almost sacred—at times, I didn’t even understand what I was doing—in that it alone could account for everything that was happening.

DH Only the broken can speak for the broken: power cannot bear witness.

YH I believe so, yes. Even Nietzsche said “You have to blush with power.”

SH It’s broken. There are fragments of truth. So there are fragments of truth because it is broken. In French, we say “deliver justice”. Your text essentially catches these fragments of truth and articulates them. In the Jewish tradition, there is the significance of shmattes, the rag or fabric, and how we stitch, restitch, unstitch, and start all over again. How do you interpret and answer the question you must have been confronted with, I’ll add a touch of Molière: “What the devil was he doing in that galley?”, knowing what role literature plays in a courtroom.

It makes me think of this well-known verse from Deuteronomy 16:20, “Pursue justice and justice alone.” This repetition is the subject of much commentary. Delphine Horvilleur once quoted Nahmanides’ interpretation in an issue of Tenou’a: “You shall pursue justice in court and you shall work for justice every day with each of your actions.” This book could be the written form of this 13th century commentary. Could “justice” be the name of what your writing seeks?

DH I’ll add that what I like about this passage is the stuttering effect. It is extremely important to the rabbi. Moses is chosen because he stutters, the spokesman has a speech impediment, and this is exactly what we’re talking about: weakness. If you aren’t vulnerable and broken, if your speech isn’t broken, you aren’t given a voice…

YH … because you aren’t listening.

It’s true that in theory, literature has nothing to do with the law. And my editor, Philippe Sollers, was astonished. He told me, “A writer doesn’t go to court!” The night after Riss suggested I go, a year before the trial, while I was fighting insomnia, I thought back to Kafka’s parable “Before the Law” contained in his novel The Trial. We always forget that it’s a priest who delivers this parable and that a sort of midrash follows. The two characters keep going back and forth. It’s ten pages long. So Riss had asked me, “Are you coming?” (hence the insomnia) and at first it was a no, because I thought that in the parable, the door to the law was closed. During the night, I got up and checked The Trial: and of course, the door was open. The door to the law is always open. I was struck by this fact, of course the door was made only for him, the door is open only for me, for each of us at every moment, and it might not even be a question of going through it, but there is a light. In the text, there is a light that never goes out, that comes from far, far away. It’s the only thing he can see: he will never enter, but he has this light. And during the night, I wrote to Riss. “I’m going.” I’m stepping through the door.

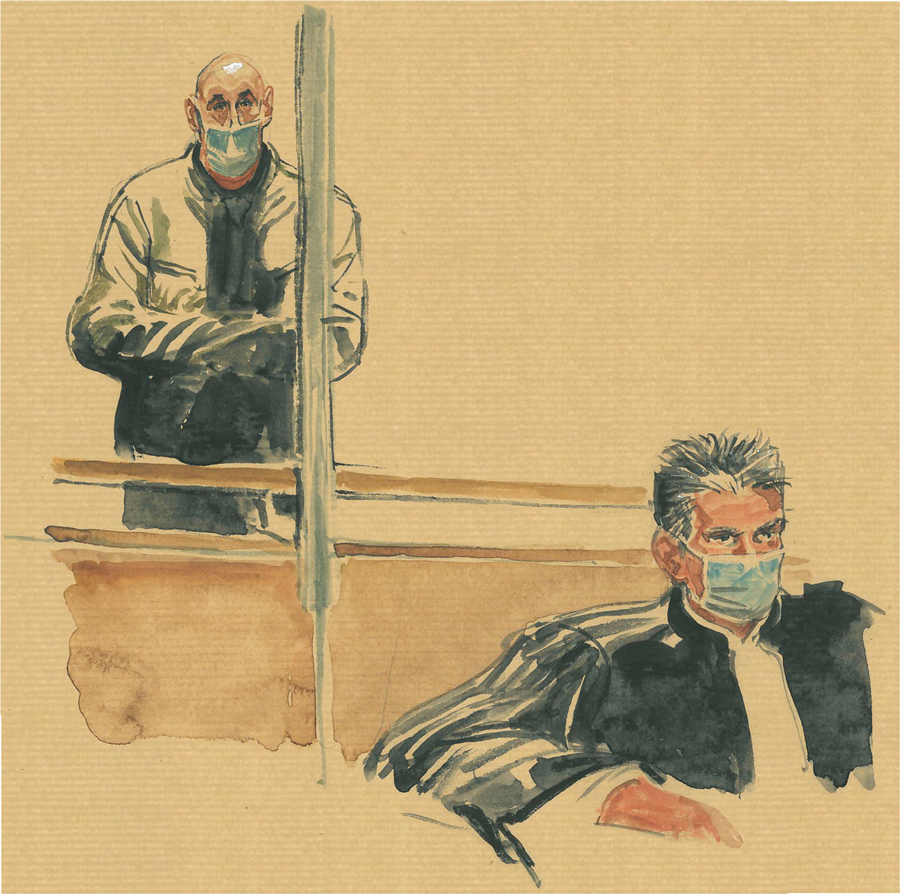

I walked into the courtroom for the first time. At no point did I believe literature could add anything, but, quite the opposite, that it was a place, a space that might match the empty space at the heart of the Law, the heart of the court, which jumped out at me within seconds, and which is that of the bar. Between the court, defendants, civilians, journalists, and lawyers, there is a white rectangle. And a transparent bar. Like in some Anselm Kieffer paintings, or like a Rothko, in a white monochrome. Not only did I see in it a page to be filled, but I also saw the freedom possible and the fact that literature—in the sense of listening to all voices and to the words being spoken—didn’t require an effort, that it was going to happen almost without me, that I was a recorder. I still had to convert every day’s proceedings. As soon as a witness came up to the transparent bar to take the oath and testify, I had to convert that into a sentence since there was no narration. I couldn’t keep my distance, this involved an exploration of the realm of storytelling. That’s what I believed justice to be: the realm of storytelling.

It was my responsibility. Because speaking for people who have been killed, speaking for people who haven’t quite been killed, speaking for people who have eluded death, speaking for people who have come to speak but do not know how, this is to bear the weight of the world, as Peter Handke would say. And it still hurts here, and here, and here, it is a physical pain. I know the exact spot in my body where Riss is, where Coco is, where Zarie Sibony is, where all the others are. And every morning at 4 a.m., before the sun rose, during the hours I spent between four and seven writing, that weight was lifted. I also weakened the literature, until this watermark, the bar’s transparency, became a filter.

DH Since 2015, I’ve been thinking a lot about how upset I was after the attacks when Charlie published the “All is Forgiven” front page. All around me, everyone seemed to fall into two categories: those who understood the headline, and those who did not, many of whom were my Jewish friends. It’s interesting, because there is a theological element in this headline that likely isn’t deliberate: in Judaism, and particularly since the Holocaust, there is this very strong notion that we cannot forgive in place of the victims. It is a theology that is much less focused on forgiveness than in Christianity. I was wondering if you came across this notion of forgiveness at any point during the trial?

YH I put myself in everyone’s shoes, which Charlie Hebdo constantly criticized me for whenever they read my work. I always thought there was something sacred about Charlie Hebdo. They keep saying no, which I hear as pure denial. The “All is Forgiven” is a grandiose gesture, and I think you, Delphine, you gave an explanation by positing that the world is split into those who make room for others and those who don’t. But I don’t think even Charlie Hebdo understood this somewhat crazy front page by Luz, who put everything out there when he finished at 3 a.m. saying “All is Forgiven” before resigning. It went so far, theologically speaking. Which is fine, because that signifier ushered us into a new world.

SH In the book, there is this sentence: “And the dead do not die as long as we speak of them, they live inside our words.” I’m wondering if this is what has been anchoring and orienting your writing for so long. Is that what you call bearing witness: that words carry names? And is this also what you mean by making words speak?

Isn’t this book in keeping with the tradition of your masterpiece Jan Karski, which opens with this quote by Celan: “Who witnesses for the witness?”? You have chosen to translate it through a question. A call. A call that you answer. Writing then makes the verbs “to write” and “to witness” inseparable, inextricable.

YH I am getting closer to the dead, and therefore to the living. I am well aware that today, more than ten years after publishing Jan Karski, I am accomplishing something that stammered its way through my love for an innocent witness, whom I did not choose at random, who was a Catholic like myself but who considered himself a Jewish Catholic, which isn’t even possible. I could say the same thing. I believe that the words that are communicated through the speaking bodies around us, those that bear witness—these words never stop deciphering the names they carry.

It’s true that this book, which I had envisioned as a book from the beginning—I’m not a journalist, I do not know how to produce an account of something in the moment, I need more time—, it is the action of hermeneutics and invocation. For me, the issue of names always conjures two things: hermeneutics, or the act of deciphering, and how or what we call them. And what struck me during the trial, in this very strange position for a writer, is that I enjoyed being there. Nietzsche wrote about “Feeling happiness down to the terror of the spirit.” I was terrified, but I felt joy by being enveloped in this terror, because the invocation that implies, the presence of all these people who continue to express themselves—at the end of the day, that can only be called love. It was up to me to stitch together these words that had allowed something to occur. I felt honoured by these words all day, and I spent three hours every night stitching something together.

DH In Genesis, this phrase recurs throughout the story of creation: “There was evening and there was morning, the first day,” “There was evening and there was morning, the second day.” In Judaism, you always count the days beginning with the night. Time is counted from sunset: the story begins if you get through the night. So what you are expressing is this creation, by occurring through the night, is that it always begins in darkness. I found the dialogue between the visuals and the text, how all the faces appear, creates a bridge between the two worlds for the reader. It felt like a permanent dialogue between these worlds, an in-between. And this reminded me of Zarie Sibony’s testimony, which upset so many people for its contrast between her grace and the horror of her words. It’s this space in between.

YH Because she was the one who managed to hold both worlds together even while the bodies were piling up around her. She managed to keep them together. I was thinking that through her, we could see not only that fragility had stood up once again to the pseudo-power of weapons, but moreover that it had defeated it; through her testimony, she had managed to come and bless, in a sense, what had been violated. Her testimony restored the sacred, which had been in tatters, to everyone.

SH I would like to pay tribute to another woman. By reading what you write about Mr. Zagury’s plea regarding the murder of Clarissa Jean-Philippe, we approach an understanding of something that illustrates what is infinite, what is unbearable (and Lacan said that “the soul is what stands up to the unbearable”) in the logic of anti-Semitism, of what makes it structural. Clarissa Jean-Philippe was, in fact, the victim of an anti-Semitic crime. And this reminded me of a quote by Levinas that haunts me: the dedication of Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence: “To the memory of those who were closest among the six million assassinated by the National Socialists, and of the millions on millions of all confessions and all nations, victims of the same hatred of the other man, the same anti-semitism.” In other words, one can be murdered by the unleashing of anti-Semitic rage even if one “is” not Jewish. Unless… There must always be quotation marks around the “is” in “is Jewish”. Or immediately risk this sentence: there is no such thing as someone who “is Jewish”. Or perhaps Sartre is right, the Jew exists only through anti-Semitism and, therefore, Clarissa Jean-Philippe, who is not Jewish, is Jewish at the same time. I wonder if this is what your text invites us to understand at this point in the book.

YH I believe that the crime against Charlie Hebdo was also an anti-Semitic crime, not only because they killed Elsa Cayat, not only because she was a woman when they said they did not kill women. But I know, and this trial has at least made it clear, that not only that day at Montrouge was meant to be an anti-Semitic crime and therefore was one, even if the victim was not Jewish. But against Charlie Hebdo, I know that it was already an act of anti-Semitism. The Kouachi brothers, we determined and the investigation showed, were people who wanted, at one time in their lives, before going to Syria, “to break some Jew”. To me, this killing made Jews of Charlie Hebdo.

Interview and direction by Stéphane Habib and Antoine Strobel-Dahan

Translated by Airelle Aaronson