Courtesy: Zemack Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv

It will begin with an early-morning macchiato at Bar San Callisto, as seagulls squawk and customers grumble. The weather will be lovely, and even if it isn’t, we will have our coffee outside on principle. Then, once the nearby church opens, we will pay homage to its golden mosaic and the crowned Virgin will speak to me of the Catholic goddess.

But perhaps we will have sworn off noisy, rowdy Trastevere—at least as a neighbourhood to live in. Remember how it was so disappointing the last time? Not one nice restaurant in five! Sure, there’s Da Teo and Taverna Trilussa, but you don’t have to live down the street to swoon over the millefoglie di pane carasau, burrata, and puntarelle we were served two years ago. And anyway, there’s nothing wrong with eating wild chicory in winter… Perhaps we will return to the Chiesa Nuova area to sleep. In the pale light of the morning, we will stroll down the Via Giulia, tripping with reunion-fuelled joy over its uneven cobblestones, plastering ourselves against its walls each time a car tries to squeeze its way through, ducking into the dilapidated courtyards of its palaces whenever possible. I will rap on the closed doors with the knocker, its metal reluctant to budge, stubborn as a toddler—and rightly so. The problem is that door knockers in Paris are lacquered shut, and in New York they do not exist. There are none in either Jerusalem or Tel Aviv, and the ones in Jaffa have all been destroyed. Using a door knocker is, for me, a purely Roman or Venetian pleasure.

I will be glad to see the Mascherone for the first time in months, behind Palazzo Farnese: his eyes will seem to open even wider in surprise than the last time we met, and the greenish water dribbling from his mouth will be more questionable than ever. The vestiges of this Latin god always seemed to me—perhaps because I often walk this section of Via Giulia in the wee hours of the morning—like a reveller staggering out of the nightclub.

Or maybe we will have begun a day earlier, at Osteria Margutta, dining outdoors under the bougainvillea or indoors under the jazzy light of the red and blue pendant lampshades. I will have ordered my tonnarelli cacio e pepe, and she her vegetable paccheri, and we would not have been able to resist either sweets or wine. Our eyes will scan the room, landing on the faces of customers and ghosts of bygone eras: over in that corner, Federico Fellini and Giulietta Masina are finishing a plate of pasta they began five decades ago. My heroes of the silver screen are Romans, when they are not New Yorkers—or Parisians if we are talking Delon, Marielle, Noiret. But these three also acted in Italian productions, and Delon even shot films such as the magnificent Purple Noon in Rome! My heroes include Sordi in A Difficult Life and Gassman in The Easy Life, Mastroianni in La dolce vita and A Special Day, and Toni Servillo in The Great Beauty. As for my heroines, they are Giulietta Masina, Anna Magnani, Sophia Loren, Silvana Mangano in Conversation Piece, Ornella Muti in First Love, Laura Antonelli in The Innocent… But I’ve been told the restaurant has closed—and I’m not quite sure if the Rome it symbolized for all these years ever really existed. Perhaps it was only ever a dream, the kind of unwieldy, outdated dream that the “next generation” seems bent on abandoning once and for all.

From the Palazzo Farnese, we might wander down Via dei Balestrari to Sant’ Andrea della Valle, whose marble reverberates with the jealousy of Tosca. From there we’ll stroll to the Largo di Torre Argentina. It would be a shame not to drift among the ruins, like in the time of Edmond Dantès, where children would play with myriad stray cats and the spirit of Caesar, assassinated there. On the one hand, the theatre would remind me of Verdi’s opening nights; on the other, Via delle Botteghe Oscure, Marguerite Caetani’s literary journal, and Giorgio Bassani.

Or instead, we may walk straight to Campo de’ Fiori where, whether empty or infused with the market’s end-of-day chaotic joy, we can still taste hints of the past that linger on the air, some sweet, some bitter. The flames that engulfed Giordano Bruno, and, fifty years earlier, thousands of pages of the Talmud, crackle in the ears of anyone listening—but the instant paper, parchment, and flesh is reignited, the letters fly up to the heavens, lost forever (Avodah Zarah, 18a).

Another morning might begin at Boccione, in the Ghetto. I’ll fill up on pizza ebraica that I’ll dip, groaning with pleasure, into a caffè I swiftly gulp down. Or maybe I’ll go for the ricotta pie, after all. The old lady behind the counter looks very tired. The kids (her grandsons?) are so Roman even Hadrian would be envious.

If later, we wind up at Via del Portico d’Ottavia—but not too late, eleven o’clock or noon at the latest—we will feast on fried lamb’s brains, concia di zucchine, carciofi alla giudia, and a glass or two of white. (It was as I watched her eat the first of these dishes on a cold February morning three years ago that I think I knew I’d marry her.) Will I go to the synagogue on Friday night to pray? It’s a shame there are no longer any small prayer houses left in the old Ghetto. They didn’t have a dome visible on the horizon like this one, but the sharp flavour of Roman Jewishness— sautéed chicory or endives, olives, and bottarga—was surely more potent there. From the time of Poppaea Sabina’s Judaization to the beggars of Subura, from the foreign upstarts who were hated by Cicero and loved by Caesar, to the lascivious sonnets of Immanuel and the novels of Morante and Piperno, Rome has never stopped being Jewish. At the Forum, I will tell Titus, as I always do, that he has lost twice over.

Across from the synagogue, the Art Nouveau frescoes of Via del Tempio: this is languorous, decadent Rome—Byzantium and Carthage—of Gabriele d’Annunzio and Mario Praz. Following in the footsteps of the Professore, I’ll go admire the Sabine women being abducted in Piazza de’ Ricci and the collections of Palazzo Primoli.

The Tiber is unlike the Seine; its waters flow wild, like a river of the New World. We will walk along it—the air heavy with the scent of figs—then climb up from its banks to wander around the base of the Palatine Hill, at the edge of the Circus Maximus (unless we choose to visit the Aventine Hill instead). The two solemn women portrayed in the mosaic at Santa Sabina tell a story, though not a happy one, that I am fond of: as the Empire is collapsing, the last pagans know it spells the end because the Barbarians are at the gates and the city will soon be sacked. The church, which combines Early Christian and Baroque architecture, gives off an energy that suits me, just like the church of San Clemente—basilica and mithraeum, paganism and Christianity intertwined.

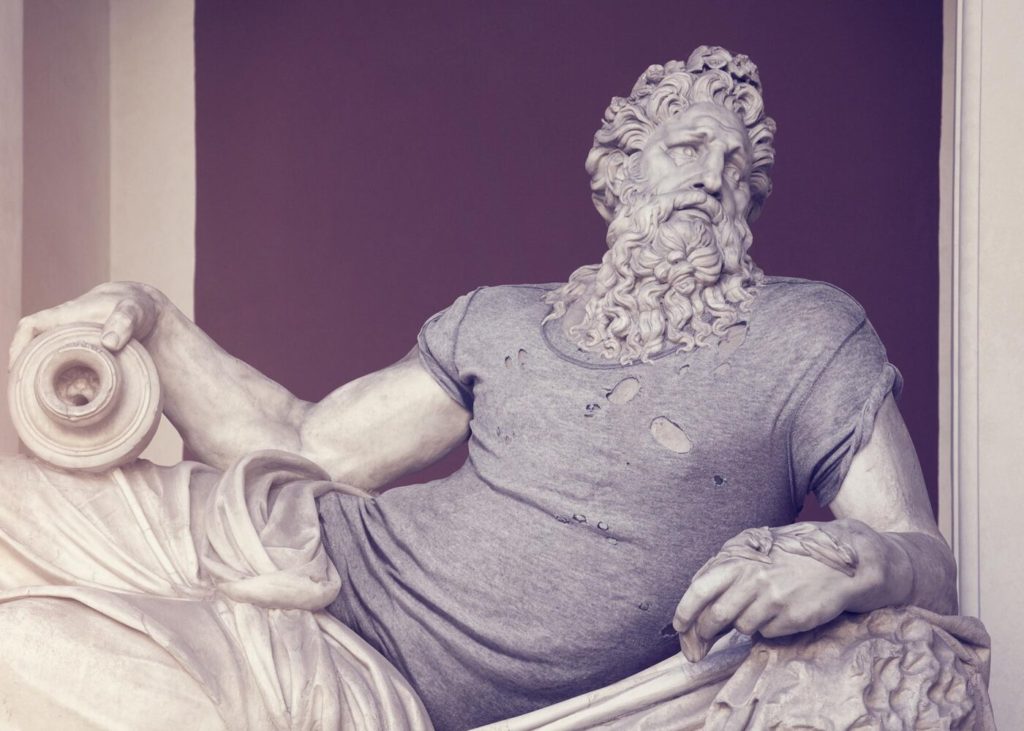

It has been years since I’ve visited Michelangelo’s Moses. From the Aventine Hill, we can easily walk to San Pietro in Vincoli, cutting through the Colosseum and Domus Aurea and breathing in the odour that persists, century after century, of the Subura of witches, whores, and poets: today is Via Cavour and its environs. This Moses, a figure of white-hot virility, is horned—but this is no joke: Jerome read it right. The prophet who made love to a goddess (Zohar I, 21b) does logically bear the horns of oriental gods. Moreover, he was buried by God’s own hands (Deuteronomy 34,6). The Jews of the Ghetto were not mistaken, writes Vasari, when they came en masse in 1515 to admire the depiction of their master.

If it rains, we will go watch the water transform the Pantheon as it drips through the oculus in its roof.

At the Doria Pamphilj Gallery, I will reconnect with Titian’s sweet Judith. She holds the head of Holofernes with the composure of a queen: her rumpled linen shirt and red silk dress slipping off her shoulder reveal a deeper story. In the background, day is breaking over a world delivered from evil; the young goddess smiles gently. And yet—perhaps she is Salome, not Judith, who has committed the irreparable with the fervour and innocence of a whim: “I want to speak to him.” “That is impossible, princess.” “But I want to. … Ah! Ah! Why did you not look at me, Jokanaan? If you had looked at me, you would have loved me. I know you would have loved me, and the mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death.”

Speaking of Salome, the Gallery also owns a Caravaggio of John the Baptist with a ram—a depiction as gracefully androgynous as the ephebes of the Sistine Chapel. How did the most Jewish of all New Testament characters end up a focus of pagan joy? Likely because the two are not as different as we think. He will smile at us, eyes full of malice, clutching his divine beast, just as a boy from Lazio was bidden to do before the eyes of a Merisi thirsty for bodies and shapes to recreate, for these shadows tinged with gold he saw everywhere.

In Rome, the countryside and city coexist—as do the past and the present. We will go visit the aqueducts of Mamma Roma, walking along the Appian Way scattered with ancient tombs. Or perhaps we will go further afield, to Nemi, Grottaferrata, or Tivoli.

I’m not sure what we’ll be looking for—possibly the golden branch, Nemi’s famous strawberries, or the superb asparagus pasta we had one April night at Taverna dello Spuntino. It had been damp and chilly despite the season, and there was a fire crackling in the enormous hearth. Hours flew by without us noticing, and by the time we left, the rain clouds had gathered. We walked back to our room through the cold, biting mist.

Next year, I’d like to see Rome again.

Translated by Arielle Aaronson