Courtesy: Galerie Éva Vautier, Nice. Galerie ANNE+, Paris – www.josephdadoune.net

“I like to remember insignificant things: they don’t prove anything, but they are life.”

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

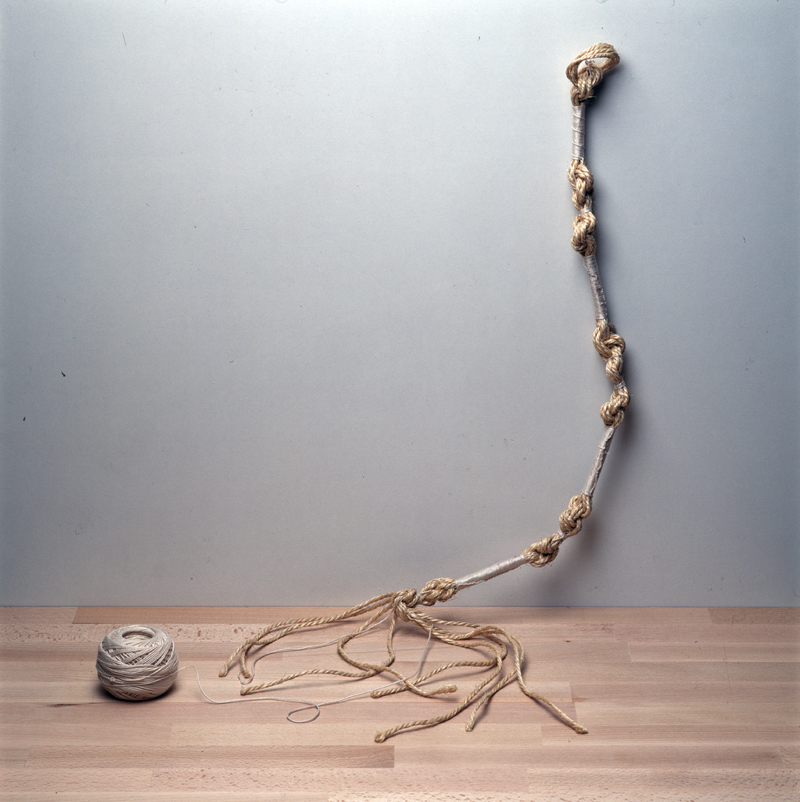

As Marcel Rufo notes in Détache-moi. Se séparer pour grandir: “Everything begins as a fusion, in which mother and child are one. A vital fusion, from which the child builds confidence and strength to set out and conquer the world. Yet growth is essential, and to do this we must distance ourselves in order to gain new spheres of independence and freedom. Children’s psychomotor development, and all human life, is a series of attachments and detachments, of conquests and separations […] Separation from the mother’s womb, separation from the breast, separation from a piece of oneself once fully toilet trained…”

To live is to separate, to leave, to abandon, to grieve. But each of these painful stages allows the child to become more free and independent.

Whether it is “separating from a nanny,” Rufo continues, “or a teacher, home, toy, pet, friend, or loved one, on every occasion the child must separate himself from one world to be able to conquer a new one. Every separation is an ordeal from which the child emerges grown and more human, an ordeal that teaches him winning is impossible if he does not accept defeat, with the thrill of the conquest soothing the pain of loss.”

Though we are unable to live without ties, the moment these ties become too exclusive, they threaten to suffocate us. We must therefore loosen them and free ourselves in order to find the right distance between ourselves and others.

Certain rites, laws, and customs in the Jewish tradition ensure that these connections, fusions, and de-fusions are managed properly.

To use Scholem’s words in reference to Abraham Abulafia’s Kabbalistic method, I would say that we are dealing with a “science of knots to untie”.

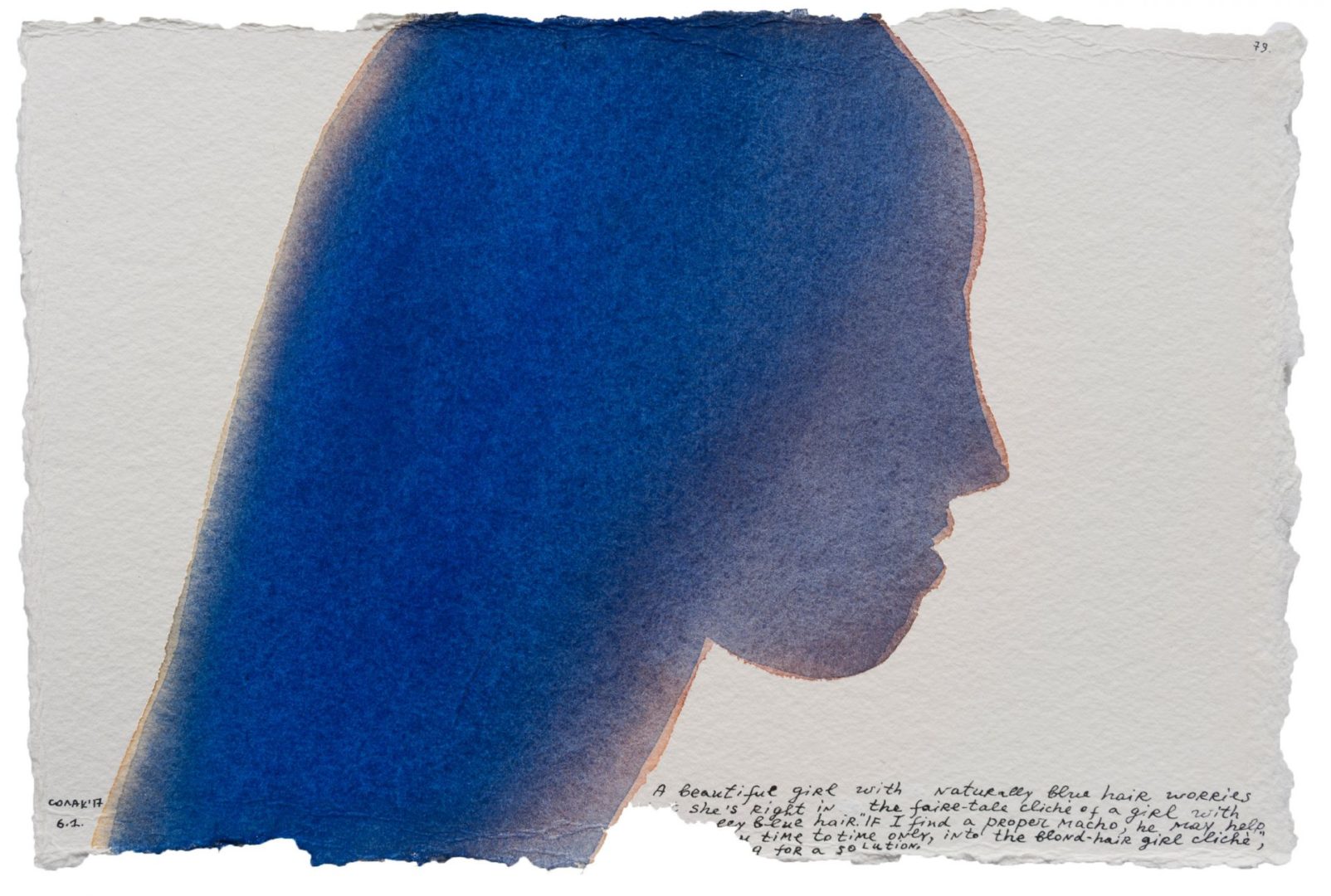

A PARADIGM OF THE KNOT QUESTION: CUTS AND HAIRCUTS

In the Jewish tradition, one recurring rite acts as leitmotif in almost all communities and exemplifies the idea of a cut being linked to separation: the haircut. It is a rite that is practiced according to custom at two significant times in the life of a child and adolescent. At three years old (or just before the child enters kindergarten) and just before their Bar/Bat Mitzvah, the father and his son and the mother and her daughter—and sometimes even friends—will get their hair cut. In some communities, these events are performed to music and are often accompanied by song, dance, and food. For both of these life events, the haircut can be seen as an act of “desistance”. (See our book, co-written with Françoise Anne Ménager, Bar-Mitsva, un livre pour grandir, Assouline, 2005).

HAIRCUT AND READING

Cutting the hair of the child entering school marks his separation from the home and the special bond the child maintains with his mother, the primary caregiver (although we know that in newer generations, fathers are becoming increasingly involved in the lives of their children). The separation from home and parents is experienced as a rupture and loss, which entry into “the world of letters” and the Book may help overcome. On this occasion, there is a custom of offering honey cakes in the shape of letters to the child as a way to associate letters, reading, and knowledge in general with something sweet and happy.

HAIR AND THE PRAYER SHAWL: THE TALLIT

The link between a haircut and reading can be seen again with the Bar/Bat Mitzvah, this special occasion when connections are made and unmade, untied and renewed. These connections can be affective, familial, community, love, educational, philosophical, ideological, and more.

I think it is important here to emphasize the relationship between hair and the ritual prayer shawl called tallit, whose four corners are knotted with fringe called tzitzit. These tassels are knotted symbolically in a number that echoes the numerical value of one of the names of God: 39. In Hebrew, this number is pronounced tal, meaning “dew”, and gives its name to the prayer shawl, tallit (see my Concerto pour quatre consonnes sans voyelles, Payot-poches).

A verse from the prophet Ezekiel establishes the correlation and the equivalence: “And He put forth the form of a hand, and took me by a lock of mine head; and the Spirit lifted me up between the earth and the heaven, and brought me in the visions of God to Jerusalem, to the door of the inner gate that looketh toward the north, where was the seat of the image of jealousy, which provoketh to jealousy.”

The translation of “a lock of mine head” is found in the verse ראשי ציצת, tzitzit roshi!

In this way the tzitzit, or the ritual fringes of the tallit, become the symbolic equivalent of hair, and we subsequently understand the importance of the shawl within the Bar/Bat Mitzvah rituals. With its ritual fringes, the tallit resembles plaits or braids you can wear on your head, wrap yourself in, and remove—and which are symbolically cut each time the rite is performed.

This also allows us to better understand why, during the hair-cutting ceremony upon entering kindergarten, the child receives his first tallit katan, a small prayer shawl he will wear at all times underneath or over top of his clothes, according to tradition. For boys and girls in liberal circles.

This is also an opportunity to point out that the word “hair” or se’ar in Hebrew, is a homograph of sha’ar or “door”. The haircut always acts as a symbolic passing through of a door, taking us from one world into another and, generally, for the best. How can we not think of Baudelaire to conclude this footnote of an upcoming book:

[…]

“Blue-black hair, pavilion hung with shadows,

You give back to me the blue of the vast round sky;

In the downy edges of your curling tresses

I ardently get drunk with the mingled odors

Of oil of coconut, of musk and tar.”

[…]

Translated by Arielle Aaronson

Courtesy: Galerie Éva Vautier, Nice. Galerie ANNE+, Paris. – www.josephdadoune.net