© Frédéric Brenner, avec la permission de la Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Before the Zionist dream became reality in the land of Israel, the quest to establish a Jewish homeland took a few unexpected detours.

At the end of the 19th century, the stirrings of nationalist movements and antisemitic persecution in Eastern Europe and elsewhere sparked a wave of Jewish migration to foreign lands, from the Argentinian Pampas to East Africa, and from North America to Soviet Siberia.

These visionaries (and the philanthropists supporting them) were either territorialists, working towards a refuge for persecuted Jews regardless of geographic location, or Zionists, focusing their efforts on Jerusalem and the biblical land of Israel. These two visions clashed regularly at Zionist congresses.

Baron Maurice de Hirsch, a Bavarian banker working in in Brussels, organized the emigration of persecuted Eastern European Jews by financing agricultural colonies in the Argentinian Pampas. At that time, Argentina was open to immigration without conditions. Europeans found its climate tolerable and its soil quality exceptional. In 1889, 136 Jewish families arrived from Podolia and settled in Moisés Ville. It was hardly El Dorado: nearly two thirds of immigrants died of hunger and exhaustion, unaccustomed as they were to hard agricultural labour. In 1891, the baron founded the Jewish Colonization Association and established other Jewish gaucho plantations—Mauricio, Sonnenfeld, Basavilbaso and others. In the estimation of Alberto Gerchunoff, who published a book entitled The Jewish Gauchos of the Pampas in 1910, Moiséville was the new Zion and Baron de Hirsch was the new Moses. The newcomers built schools, a theatre and a library, published newspapers in Yiddish and Spanish, and offered Hebrew classes. In 1923, the population numbered 8,826, of which 7,400 were Jews, and more land was being purchased every day. This vision of Judaism was brawny, a countryman’s Judaism on horseback. Today, all that remains is a cemetery, a handful of Jewish witnesses to the past, and a small museum.

In parallel to the Argentinian project, Theodore Herzl, who had been profoundly marked by the antisemitism of the Dreyfus Affair, was also working himself to the bone in search of a sanctuary for persecuted Jews. The “Jewish State” he envisioned should be located wherever it was possible. He considered Egypt first (El-Arish, 1903), but abandoned the idea because the Sinai Desert wasn’t suited to agricultural development. A few months later, Herzl and his partners Max Nordau and Leopold Greenberg proposed an East African option to the Sixth Zionist Congress in Basel. The Nairobi Plan was approved by a majority, but it polarized Zionist attitudes even more. An exhausted Herzl died six months later, while Nordau dodged an assassination attempt. The colonial British government thwarted the Nairobi Plan, but Greenberg didn’t give up, and in 1905 organized an expedition to Uganda. Sadly, wild animals and epidemic risk (bubonic plague and malaria) soon put an end to the explorers’ enthusiasm.

In the same year, the English writer Israel Zangwill founded the Jewish Territorialist Organization, with support from the Rothschilds, Winston Churchill and other prominent figures. The JTO was tasked with investigating suitable territories for a Jewish colony in any peaceful country; they investigated a long list of possibilities, including Cyrenaica, Angola, Brazil, Paraguay, Nevada, Australia, Siberia, Mesopotamia, Manchuria, Cuba and Canada. It’s well worth reading the pages of Les Terres promises avant Israël by Olivier de Marliave (Imago, 2017) devoted to these territorialist dreams. When Zangwill died in 1925 and the JTO was dissolved, these territorialist projects too were abandoned.

The push to establish Jewish colonies was often imbued with utopian socialism; Yiddish eclipsed Hebrew, trade unionism became the new religion, and kosher butchers were less in demand than labourers (read Terre Promise by Nathan Weinstock, Metropolis 2001, about the Jewish labour movement overseas). Today, small groups of Russian Jews can be found in California, the Rockies, Louisiana, Texas (the Galveston Movement) and upstate New York. In 1825, a man named Mordecai Manuel Noah founded a modest colony called Ararat on the banks of Lake Erie, at the border between the United States and Canada. But dreams once again collided with harsh reality, and the Ararat project foundered too.

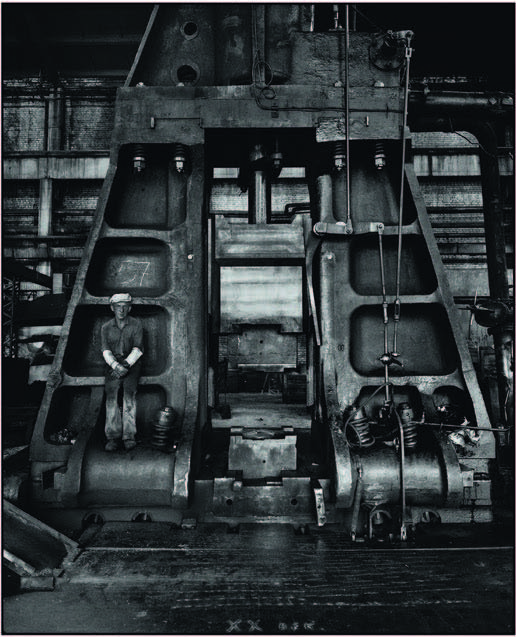

The vision of an autonomous Jewish homeland now moved east towards Russia, where creating agricultural Jewish colonies was seen as a way to simultaneously “solve the Jewish problem,” and reinvigorate ailing agriculture. After an aborted project in Crimea in the 1920s (with Jewish American financing!), the idea of a Jewish autonomous region emerged once again—but this time in a remote no man’s land between China and Russia called Birobidzhan. Everyone got involved: Stalin, with his policies against minorities, territorialists like Zangwill and the successors of Herzl, and all others who were seeking a place for Jews to safely live. Between 1928 and 1938 over 40,000 people moved to the Jewish Autonomous Region, first into barracks and then kolkhozes. There were advertising campaigns (“a land of free-flowing honey”), glowing articles in the Yiddish press of Paris and New York, and foreign donors encouraging immigration to Birobidzhan. On the ground, however, agriculture soon dwindled, while industrial and metallurgical work increased. Stalin intended to establish 300,000 people in the autonomous region; in reality, even in its best years, population never exceeded 43,000. The inhabitants, mostly foreigners, became disillusioned and departed. Culturally, Birobidzhan was a failure as well. The promotion of Yiddish as the region’s national language (the language of schools, theatres, the press, libraries, and official communications) didn’t take. In fact, Yiddish was a tool used in service of socialism to promote militant atheism, erase distinctive Jewish identity, and transform each individual into a homo sovieticus. The “land of honey” was not spared the Stalinist purges, arbitrary imprisonments, the suppression of Yiddish in favour of Russian, and other hardships. On the eve of the war, Birobidzhan looked more like an example of political and cultural failure than the realization of a utopia. Birobidzhan still exists today, but it’s no longer an autonomous region, and no elements of its ancient Jewish past have been retained, except for a few rusty signs written in Yiddish.

Translated by Emma Roy