I always adored my grandfather Aissa. He had all the qualities a grandfather should: he was tall, he was strong, and he was wise. Family legend has it that he came to Tangier on foot from his childhood home in the Rif, in north-eastern Morocco. He travelled at night to evade the French soldiers. He was a hero, my grandfather Aissa, but despite all his virtues, there was one thing about him I didn’t like—he was constantly itching to leave a place from the moment he got there. “It’s not the destination that matters,” he’d say, “it’s the journey.”

To me, this is crazy. To me, there’s never been anything more noble than getting there, more important than the end goal … until the day I discovered Cordoba.

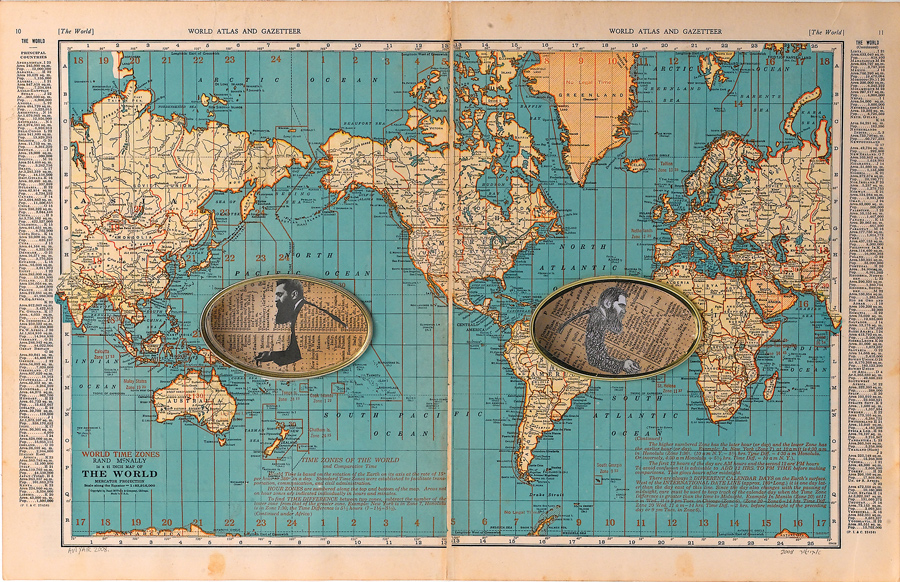

As the son of a Moroccan immigrant, the seven letters of this Andalusian city’s name are part of me. Every year, our parents took us to Morocco to “reconnect with our origins.” The journey was long, and at that time, dangerous; some never returned. It meant going through France, traversing Spain from north to south, and crossing a strait, all for the privilege of treading on the sands of the Kingdom of all kingdoms.

Nearing the end of the trek, after we’d counted all the bull-shaped billboards that dotted the Andalusian plains, that magical road sign would finally appear before our eyes: “Cordoba.” Once we spotted the sign, we knew we were only two hours from the port and the end of the journey. My father would tell us about Cordoba, which he’d visited when he was a teenager, and even suggest making a brief stop—but that was out of the question. We wanted to get to Morocco; what mattered to us was the final destination, not the things along the way. And so Cordoba remained, for me and for thousands of Moroccan immigrants, merely a sign indicating the proximity of our deliverance.

Just a worthless old sign. Seven letters. Nothing more.

Until at age 38, I decided to see what was on the other side of the sign. I arrived in Cordoba not knowing what to expect. All I knew was that I had to make the stop, even if only that once. Morocco had always been my destination, my promised land, as Israel was for Moses —but what if, for once, I didn’t go?

What if, just this once, I stopped along the way? What if, just this once, I understood that the promise of the Lord merely served to propel me forward, that the promise was in what I would find on the journey?

What if the promise was just the impetus, the destination only an excuse, and arrival no more than a delusion chimera?

When I reach the Roman bridge before the city of Cordoba, all of these thoughts are jostling around in my head. What strikes me first are ramparts, which aren’t forbidding but welcoming, reaching out to a stranger like a warm, solid embrace. Past the wall I discover the Mezquita, the most misbegotten building in the history of humanity: a church built in a mosque which itself is built on a temple. There is a crucifix tucked into a mihrab, facing Mecca. Is this blasphemy? Or is it simply a reflection of ourselves: an accumulation of histories and civilizations, impossible to disentangle?

I leave the Mezquita to walk along the narrow street that surrounds and protects it, the Judería. A Jewish quarter surrounding a mosque. The city is confirming for me that God has a sense of humour. In Jerusalem, Jews talk to Him in front of a wall topped with an esplanade where other people talk to Him in a different language.

Lost in my reveries about God’s preferred language, I find myself in front of a statue. A man wearing a turban and carrying a Quran sits enthroned before me. He looks majestic, respected, respectable. His gaze seems fixed on the horizon.

It’s only upon reading the plaque embedded in the marble that I discover this turbaned Arab is holding a Torah, not a Quran. The man is Jewish, and his name is Moses Maimonides.

Is he Jewish or is he Arab? What camp should I put him in? I head into the Casa de Sefarad to get answers.

Entering the Casa de Sefarad, I’m met with a synagogue tour group, and I allow myself to be carried along with their flow. In the synagogue, I realize that everything is written … in Arabic. It looks just like a mosque! I knew God had a sense of humour, but this … I mean, he could do stand-up!

Jews, Arabs … I don’t understand anything anymore. And the tour guide must have a sudden desire to add to my confusion, because he offers me a little explanatory pamphlet in which I discover that Maimonides’ magnum opus was written in “Judeo-Arabic” (that’s a thing?) and that it’s called the “Guide for the Perplexed.”

Um … God? This is more than a few jokes … we’re into comedy sketch territory here!

You want more? Here’s a man driven from his home in Andalusia to find himself in the Maghreb and then Egypt, where he serves as secretary to Saladin, and wields considerable influence on the Arab-Muslim world. And it goes on ….

Just like Averroës—whether before him or after, we’ll never know, so there’s yet another thing to argue about for you—Maimonides set reason and faith on equal footing.

Without reason, faith is blind and without faith, reason is lost.

All of this had remained hidden behind the sign for Cordoba, which had, until then, signalled nothing more than my imminent arrival in the promised land.

But what if…

What if the promised land wasn’t the most important thing, but rather the things along the way?

God promised Jordan to Moses, but it was in the desert that he was fulfilled and departed the world.

God promised life to Jesus, but it was on a cross that he was fulfilled and departed the world.

God promised Mecca to Muhammad, but it was in Medina that he was fulfilled and departed the world.

God promises a lot of things but doesn’t always deliver. Either he simply doesn’t keep his promises—although since he wasn’t elected by universal suffrage he’s not bound to them—or the promise is just the catalyst that makes us take to the road …

to embark on an odyssey beyond ourselves

to see what lies elsewhere, because it’s elsewhere that God can be found … perhaps …

Because as long as we’re on the road, as long as we haven’t reached our promised land, we’re just wanderers far from home, and we can’t forget that we ourselves have been “strangers in the land of Egypt.”

Because strangers are those who never forget where they come from, who don’t know where they’re going, but whose gaze is always fixed on the horizon, their promised land.

Like the statue of Maimonides.

What if that’s what our promised land is: the horizon!

A place we’ll never reach, a place that exists but is always moving, so that we’ll keep moving too.

What if the road to Morocco was just an excuse, a catalyst, so I’d pass through Cordoba?

So I’d discover all of this.

So I’d learn that my origins are here, not there.

This, all of this, is why I dream, why I’ve started singing …

“Next year in Cordoba.”

Translated by Emma Roy